On March 31, Carlo Rubbia, Noble Price winner and former CERN director general, celebrated his 90th birthday. On this occasion, CERN organized a scientific symposium on October 18, which Red Baron, only 14 months younger than Carlo, attended.

On that day, I took the southbound ICE 271* at 8:05 from Freiburg to Zürich, changed trains at Basel, and arrived in Geneva at 11:47.

*Intercity-Express

Some recollections of my encounters with Carlo flooded back during this train journey.

Professor Rubbia was my director general (DG) from 1989 to 1993, but I met him first in the late 1960s when he was already an ambitious physicist. At that time, CERN's high-energy workhorse was the 26 GeV Proton Synchrotron (PS), which spit its secondary particle beams into the East experimental hall.

Carlo had an experiment in that hall and insisted on having access to an area around his beamline. However, measurements of my radiation protection section showed that radiation levels were too high to allow access.

In those times, the radiation protection rules at CERN were as follows:

My section reported to the divisional radiation protection officer (RSO of the PS Division). The PS-RSO, Jack F., was a former British colonial officer with a stiff lip. His yellow fingers stuck out because he was a heavy smoker of unfiltered Navy Cut cigarettes. As a youngster at CERN, I liked and even admired Jack, for he spoke perfect Queen's English. We met over a cup of coffee several times during the week to discuss the radiation situation around the PS accelerator.

Suddenly, we three stood in the East Hall on top of concrete shielding blocs: Carlo requesting access to his beamline, the PS-RSO Jack F. denying and, in his perfect English, arguing with Carlo, and me, the physicist who had delivered the measured dose levels. They exchanged strong arguments, but Carlo accepted my interjections because I was a physicist.

Eventually, the two men agreed on a compromise I could accept as the radiation protection guardian. But the whole affair left a bitter aftertaste.

The second time I ran into Carlo was in a hallway in the spring of 1989. He stampeded out of his office and caught me, "Look what Fleischman and Pons do in the States, and we all are sleeping here," waving the paper of Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons in his hands titled "Electrochemically Induced Nuclear Fusion of Deuterium."

In the following days, I provided him and other teams at CERN with neutron detectors so that my RP-Group could hardly fulfill its radiation protection tasks. And, yes, even Cold Fusion, if it works, will produce radiation!

To make the fusion story short, eventually, a CERN spokesman said

that "essentially all" attempts in Western Europe to reproduce Fleischmann's

and Pons's results had failed. This means that Cold Fusion did not, and I add

that it will not work. Red Baron blogged on cold fusion in 2011.

My third encounter with Carlo was an indirect telephone contact in the early spring of 1990. I was on my way to a scientific meeting on radiation dosimetry at Gaussig near Dresden and had, exceptionally, taken my car. While on my way and following Germany's reunification, I wanted to see as much as possible of the now accessible parts of my home country that are regarded as Germany's heartland.

I was just climbing the Kyffhäuser monument when my mobile telephone rang. The DG's secretary called, "He wants to see you in his office at 2 o'clock."

I answered that I couldn't make it because I was traveling in Germany, but the DG could always contact my deputy at CERN. On my return, the latter told me he had discussed the query with the DG on the phone. Apparently, he had answered to Carlo's satisfaction so I could finish my travel to Gaussig without further disturbance.

My last physical encounter with Carlo was during a presentation* I gave to the CERN Directorate on the existence of radioactive waste at our premises. CERN's host countries, France and Switzerland, requested a report on the quantity concerned.

*My first PowerPoint presentation

When high-energy particles hit matter, radioactivity is created by spallation of nuclei and neutron interactions. However, unlike radioactive waste produced by nuclear fission in power reactors, radioactivity from accelerator operation has low specific activity and a short half-life.

Nevertheless, the specific and total radioactivity in tons of steel, aluminum, copper, and concrete kept on the CERN premises and waiting to be disposed of is too high to be released into the environment simply.

My third encounter with Carlo was an indirect telephone contact in the early spring of 1990. I was on my way to a scientific meeting on radiation dosimetry at Gaussig near Dresden and had, exceptionally, taken my car. While on my way and following Germany's reunification, I wanted to see as much as possible of the now accessible parts of my home country that are regarded as Germany's heartland.

I was just climbing the Kyffhäuser monument when my mobile telephone rang. The DG's secretary called, "He wants to see you in his office at 2 o'clock."

I answered that I couldn't make it because I was traveling in Germany, but the DG could always contact my deputy at CERN. On my return, the latter told me he had discussed the query with the DG on the phone. Apparently, he had answered to Carlo's satisfaction so I could finish my travel to Gaussig without further disturbance.

My last physical encounter with Carlo was during a presentation* I gave to the CERN Directorate on the existence of radioactive waste at our premises. CERN's host countries, France and Switzerland, requested a report on the quantity concerned.

*My first PowerPoint presentation

When high-energy particles hit matter, radioactivity is created by spallation of nuclei and neutron interactions. However, unlike radioactive waste produced by nuclear fission in power reactors, radioactivity from accelerator operation has low specific activity and a short half-life.

Nevertheless, the specific and total radioactivity in tons of steel, aluminum, copper, and concrete kept on the CERN premises and waiting to be disposed of is too high to be released into the environment simply.

The

discharge of CERN's low-level radioactive waste into the national depositories

of France and Switzerland is costly, and the Directorate must decide how to

spend the money.

Back to my trip.

I took the streetcar to CERN and wanted to book into the CERN hostel, but my room was not ready. So, at around 1 pm, I left my luggage in a locker and went to the Main Building.

Back to my trip.

I took the streetcar to CERN and wanted to book into the CERN hostel, but my room was not ready. So, at around 1 pm, I left my luggage in a locker and went to the Main Building.

The auditorium was prepared but still empty. I chose my seat in the middle of row four to have a clear view of the projection screen during the lectures, taking photos for this blog.

I left my coat on the seat and went to the cafeteria to get something to bite on. When I returned half an hour later, the lecture hall was already well-filled. Surprisingly, I noticed they had reserved a seat for Carlo in row three just before me.

I took my seat and suddenly found myself surrounded by Italians. I have always admired and still admire not only Italian culture and cuisine but also Italian physicists, who at CERN had the most brilliant ideas following the footsteps of Galileo Galilei's heritage. However, when it came to the realization, they needed the help of i tedeschi e i britannici.

Suddenly, the people in the row in front of me stood up. Carlo arrived and did

lots of handshaking with his compatriots on his way to his seat, but he didn't

catch my eye.

I could barely see CERN's present Italian DG, Fabiola Gianotti. As chairwoman, she welcomed the participants of the symposium in English

and opened the session.

Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith, CERN's DG from 1994 to 1998, started the series of lectures.

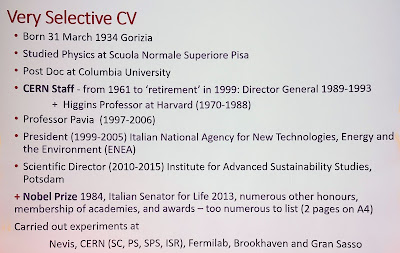

Chris showed one very selective curriculum vitae of Carlo.

On June 8, 1978, CERN's Executive Board officially decided to proceed with the p-pbar project and UA1 (Carlo's experiment)

At 5 am on July 10. 1981, collisions were observed in UA1.

Meanwhile, on July 1. 1983, the HEPAP* pushed for a 40 TeV Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) in the US to "regain US leadership."

At the BNL* 1983 Summer School, Carlo said of a luminosity as high as 1033, "It is a matter of learning how to handle it."

What was needed most urgently was a direct observation of the W±

and Z0

vector particles.

Some theorists warned that the predicted particles would be too heavy to ever be observed, but Carlo emphasized, "Theorists should not worry. If these particles exist, we experimentalists will find them."

But here we are not very successful.

Astronomy - Red Baron would say Astrophysics - is doing better.

Before the p-pbar collider became a reality, groundbreaking R&D work had to be done. Lyn Evans, former LHC project leader, centered his talk around the stochastic cooling of proton and antiproton beams. This "cooling" will narrow the transverse momentum distribution within a bunch of charged particles by detecting fluctuations in the momentum and applying a correction.

Here is a photo of the ICE* installation, the Initial Cooling Experiment at CERN.

Beam cooling allows particle densities to be achieved sufficient to observe a

high rate of proton-antiproton collisions. And cooling worked!

The W bosons are named after the weak force.

The Z boson is named after its electrical neutrality (zero charge).

|

| Carlo had headphones on, and I wore my hearing aid. |

Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith, CERN's DG from 1994 to 1998, started the series of lectures.

Chris showed one very selective curriculum vitae of Carlo.

He and Carlo first met in October 1982 as founding members of the SPSC*.

Chris recollects,

"I was immediately impressed by the enormous breadth of his knowledge of

physics, detectors, and accelerators, his quickness - he grasped points

before anyone else - and his originality and deployment of English."

*Super Proton Synchrotron Committee

In early 1977, Carlo Rubbia wrote a report on the feasibility of proton-antiproton (p-pbar) collisions in the SPS and, on March 1, invited 30 physicists at CERN and in its Member States to a study week to discuss a possible detector.

In early 1977, Carlo Rubbia wrote a report on the feasibility of proton-antiproton (p-pbar) collisions in the SPS and, on March 1, invited 30 physicists at CERN and in its Member States to a study week to discuss a possible detector.

Opposition to the project came from a number of people who argued that at

a time of economic stringency, CERN should not do something which would

otherwise be done by Fermilab (USA) and others ...

(John) Adams

countered this by pointing out that in the SPS machine, not only were the

magnets more reliable, but the greatly superior vacuum would give a beam

lifetime of 18 hours, compared to 150 seconds at Fermilab.

On June 8, 1978, CERN's Executive Board officially decided to proceed with the p-pbar project and UA1 (Carlo's experiment)

At 5 am on July 10. 1981, collisions were observed in UA1.

Meanwhile, on July 1. 1983, the HEPAP* pushed for a 40 TeV Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) in the US to "regain US leadership."

*High Energy Physics Advisory Panel in the US.

CERN countered with the LHC, which has only 14 TeV but a higher

luminosity, i.e., the number of possible collisions.

This luminosity/energy trade-off had to be understood, but it was questioned whether a luminosity of 1033 cm2 s-1 could be used.

This luminosity/energy trade-off had to be understood, but it was questioned whether a luminosity of 1033 cm2 s-1 could be used.

At the BNL* 1983 Summer School, Carlo said of a luminosity as high as 1033, "It is a matter of learning how to handle it."

*Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, NY.

Today, the LHC's luminosity is up to 2 x 1034 cm2 s-1 and is expected to increase to 5 - 7.5 x 1035 cm2 s-1 in the future.

After Carlo became DG on January 1, 1989, he stressed that compared to the SSC

- the higher luminosity would largely compensate for the lower energy

- LHC would also offer heavy ion collisions at unprecedented energy and ep collisions (the intention then being to leave LEP in place).

In 1974, the situation in physics was summarized as scenario zero: there

is nothing more than the particles we now have in our models, which we

call the Standard Model.

Today, the LHC's luminosity is up to 2 x 1034 cm2 s-1 and is expected to increase to 5 - 7.5 x 1035 cm2 s-1 in the future.

After Carlo became DG on January 1, 1989, he stressed that compared to the SSC

- the higher luminosity would largely compensate for the lower energy

- LHC would also offer heavy ion collisions at unprecedented energy and ep collisions (the intention then being to leave LEP in place).

|

| Noble Prize winner Gerard 't Hooft during his video presentation |

|

| Gerard's Standard Model |

Some theorists warned that the predicted particles would be too heavy to ever be observed, but Carlo emphasized, "Theorists should not worry. If these particles exist, we experimentalists will find them."

In 1982 and 1983. these particles were observed in p-pbar collision at

CERN.

Gerard added, "I wish theoreticians could say, 'Experimentalists should not worry; we'll make a theory that explains what you are finding.'"

Gerard added, "I wish theoreticians could say, 'Experimentalists should not worry; we'll make a theory that explains what you are finding.'"

But here we are not very successful.

Astronomy - Red Baron would say Astrophysics - is doing better.

Before the p-pbar collider became a reality, groundbreaking R&D work had to be done. Lyn Evans, former LHC project leader, centered his talk around the stochastic cooling of proton and antiproton beams. This "cooling" will narrow the transverse momentum distribution within a bunch of charged particles by detecting fluctuations in the momentum and applying a correction.

Here is a photo of the ICE* installation, the Initial Cooling Experiment at CERN.

* Another and different ICE

The W bosons are named after the weak force.

The Z boson is named after its electrical neutrality (zero charge).

|

|

Note the handwritten measurement protocol.

|

|

| Carlo at the overhead projector |

|

| Carlo's finger on the overhead foil points to the theoretically predicted value of the W-Boson. |

Carlo said, "That is to be compared with the Weinberg Salam prediction, which is 82.1

± 2.4 GeV/c2, including all the higher corrections … So we

would like to quote this number (mW = 81 ± 5 GeV/c2)

to be compared with that number (mW = 82.1 ± 2.4

GeV/c2), which, by the way, is not so bad." Carlo followed his announcement with a relieved chuckle.

|

|

One day later. In the middle, Herwig Schopper. He was my DG from 1981 to 1988. On the photo on the left are Carlo and Simon van der Meer. On the right, Erwin Gabathuler and Pierre Darriulat of the competing UA2 experiment |

|

| Prof. Zoccoli garnished his presentation by quoting Rolling Stones' texts. |

>

|

| Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer |

|

|

CERN's former DG, Luciano Maiani (1999 to 2003), expressed what

everybody felt. |

|

|

Prof Zoccoli awards Prof Carlo Rubbia the INFN Medal for the Anniversary of the Discovery of the W and Z Bosons. |

|

| French President François Mitterrand awards Carlo the Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur. |

|

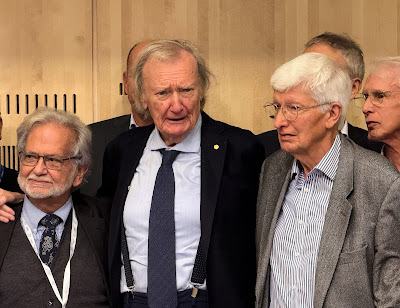

| Ultimately, Carlo's former collaborators came forward to frame the Jubilarian. |

|

| A close-up |

|

| Carlo's closing remarks ended in rapturous applause. |

He looked at me and countered, "I was responsible for radiation protection." He was so right. At CERN, the DG is responsible for everything that happens in

the Organization. So, I hastily added, "I was head of the radiation

protection group." He briefly smiled at me and then turned to a more

familiar face speaking Italian.

I have not forgotten Carlo's ideas on an energy amplifier and

superconducting power lines. These topics were discussed at the symposium,

but a presentation here would overload the blog. I will perhaps report on

this later. Here is a short foretaste of the

Rubbiatron

presented in a blog in 2011.

*

No comments:

Post a Comment