|

|

I read all kinds of things about you. All illustrations are from Professor Frick's lecture |

Retired Werner Frick was a Professor of German Studies at the University of Freiburg and is now the spiritus rector of the Studium generale, which also includes the lectures of the Saturday University covering a range of topics.

In recent years, for example, a series of lectures has been held on the 70th anniversary of Germany's Basic Law (Constitution), Resilience, and Education Today. This Winter Semester, wine will be explored in all its facets.

And he continues with his wine recommendation: "Goethe, who will also be the subject of the lecture, would have recommended his beloved 'Eilfer,' a Rheingau Riesling from the 1811 vintage of the century - that could be expensive fun today (and ultimately just a mixed pleasure). So I would recommend a witty Gewürztraminer from local latitudes to go with the cheerful drinking songs of the Anacreontic variety and would serve a full-bodied, profound red wine with the darker-toned wine poems by Baudelaire, Hofmannsthal, and Pablo Neruda: From Amarone to Zinfandel, wide noble varieties fit!"

As expected, the lecture hall was packed to the last seat, and Professor Frick's lecture was outstanding. In the following, I shall present most of the poems in German together with my humble translation into English.

|

| Portrait of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in 1755 by Johann Heinrich Tischbein |

Previously, Red Baron associated Anacreontic with the German poet

Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim.

Anacreontics,

with its eight-syllable lines, is a playful style of German and European

poetry in the mid-18th century (Rococo) named after the ancient Greek poet

Anacreon (6th century BC).

|

Die Gewißheit Ob ich morgen leben werde, Weiß ich freilich nicht; Aber, wenn ich morgen lebe, Daß ich morgen trinken werde, Weiß ich ganz gewiß. |

The certainty Whether I shall live tomorrow, I certainly do not know; But if I live tomorrow, That I will drink tomorrow, I know for sure. |

|

Die Stärke des Weins Wein ist stärker als das Wasser: Dies gestehn auch seine Hasser. Wasser reißt wohl Eichen um, Und hat Häuser umgerissen: Und ihr wundert euch darum, Daß der Wein mich umgerissen? |

The Strength of Wine Wine is more potent than water: Even its haters confess this. Water may tear down oaks, And has torn down houses: And ye marvel at it, That wine has overthrown me? |

|

Der alte und der junge Wein Ihr Alten trinkt, Euch jung und froh zu trinken: Drum mag der junge Wein Für euch, ihr Alten, sein. Der Jüngling trinkt, Sich alt und klug zu trinken: Drum muß der alte Wein Für mich, den Jüngling, sein. |

The Old and the Young Wine You old people drink, To drink yourselves young and happy: Therefore, may the young wine Be for you, old people. The young man drinks, To drink himself old and wise: Therefore, the old wine must Be for me, the young man. |

|

An den Wein Wein, wenn ich dich jetzo trinke, Wenn ich dich als Jüngling trinke, Sollst du mich in allen Sachen Dreist und klug, beherzt und weise, Mir zum Nutz, und dir zum Preise, Kurz, zu einem Alten machen. Wein, werd' ich dich künftig trinken, Werd' ich dich als Alter trinken, Sollst du mich geneigt zum Lachen, Unbesorgt für Tod und Lügen, Dir zum Ruhm, mir zum Vergnügen, Kurz, zu einem Jüngling machen. |

To the Wine Wine, if I drink you now, When I drink thee as a young man Thou shalt be my guide in all things Cheeky and clever, bold and wise, For my benefit and for your praise, In short, make me an old man. Wine, when I drink you in the future, I will drink you as an old man, Thou shalt make me inclined to laugh, Unconcerned for death and lies, For your glory, for my pleasure, In short, make me a young man. |

|

Die Beredsamkeit Freunde, Wasser machet stumm: Lernet dieses an den Fischen. Doch beim Weine kehrt sichs um: Dieses lernt an unsern Tischen. Was für Redner sind wir nicht, Wenn der Rheinwein aus uns spricht! Wir ermahnen, streiten, lehren; Keiner will den andern hören. |

Eloquence Friends, water makes dumb: Learn this from the fish. But with wine, it is reversed: Learn this at our tables. What orators we are not, When the Rhine wine speaks from us! We exhort, argue, teach; No one wants to hear the other. |

|

Der Tod Gestern, Brüder, könnt ihr's glauben? Gestern bei dem Saft der Trauben, (Bildet euch mein Schrecken ein!) Kam der Tod zu mir herein. Drohend schwang er seine Hippe, Drohend sprach das Furchtgerippe: Fort, du teurer Bacchusknecht! Fort, du hast genug gezecht! Lieber Tod, sprach ich mit Tränen, Solltest du nach mir dich sehnen? Sieh, da stehet Wein für dich! Lieber Tod, verschone mich! Lächelnd greift er nach dem Glase; Lächelnd macht ers auf der Base, Auf der Pest, Gesundheit leer; Lächelnd setzt er's wieder her. Fröhlich glaub' ich mich befreiet, Als er schnell sein Drohn erneuet. Narre, für dein Gläschen Wein Denkst du, spricht er, los zu sein? Tod, bat ich, ich möcht' auf Erden Gern ein Mediziner werden. Laß mich: ich verspreche dir Meine Kranken halb dafür. Gut, wenn das ist, magst du leben: Ruft er. Nur sei mir ergeben. Lebe, bis du satt geküßt, Und des Trinkens müde bist. O! wie schön klingt dies den Ohren! Tod, du hast mich neu geboren, Dieses Glas voll Rebensaft, Tod, auf gute Brüderschaft! Ewig muß ich also leben, Ewig! denn, beim Gott der Reben! Ewig soll mich Lieb' und Wein, Ewig Wein und Lieb' erfreun! |

Death Yesterday, brothers, can you believe it? Yesterday, with the juice of the grapes, (Imagine my horror!) Death entered. Menacingly, he swung his scythe, Threatening spoke the fearful skeleton: Away, you dear Bacchus servant! Out, you have had enough carousing! Dear Death, I said with tears, Should you long for me? Look, there's wine for you! Dear Death, spare me! Smiling, he reaches for the glass; Smiling, he empties it on the base, On the plague and health; Smiling, he sets it down again. Cheerfully, I believe myself liberated, As he quickly renews his threat. Fool, for your glass of wine Thinkest thou, saith he, to be rid? Death, I prayed, I on earth I like To become a physician. Let me: I promise you, Half of my patients. Well, if that is, you may live: He cries. Only be devoted to me. Live until you've kissed your fill, And are tired of drinking. Oh, how beautiful this sounds to the ears! Death, you have given me a new birth, This glass full of the vine's gift, Death, to good brotherhood! Eternally must I live, Eternally! for, by the God of the vines! Eternally shall love and wine delight me, Eternally shall wine and love delight me! |

|

Eine Gesundheit Trinket Brüder, laßt uns trinken Bis wir berauscht zu Boden sinken; Doch bittet Gott den Herren, Daß Könige nicht trinken. Denn da sie unberauscht Die halbe Welt zerstören, Was würden sie nicht tun, Wenn sie betrunken wären? |

One health Drink, brothers, let us drink. Till we sink intoxicated to the ground; But pray to God, the Lord That kings may not drink. Since they, when not drunk, Destroy half the world What would they do, If they were drunk? |

|

Der trunkne Dichter lobt den Wein Mit Ehren, Wein, von dir bemeistert, Und deinem flüß'gen Feu'r begeistert, Stimm ich zum Danke, wenn ich kann, Ein dir geheiligt Loblied an. Doch wie? In was für kühnen Weisen Werd' ich, o Göttertrank, dich preisen? Dein Ruhm, hör' ihn summarisch an, Ist, daß ich ihn nicht singen kann. |

The Drunken Poet Praises the Wine With honors, wine mastered by you, And thrilled by your flowing fire, I'll sing thanks if I can, A sacred song of praise to thee. But how? In what bold ways Shall I praise thee, gods' potion? Your glory, listen to it in summary, It is that I cannot sing it. |

|

|

Poet Robert Gernhardt's Confession: Bottle of wine, bottle of

wine will soon be empty. Because I need only one bottle per poem, no more. |

Getting drunk did not happen to

Robert Gernhardt, who needed only one bottle to write a poem.

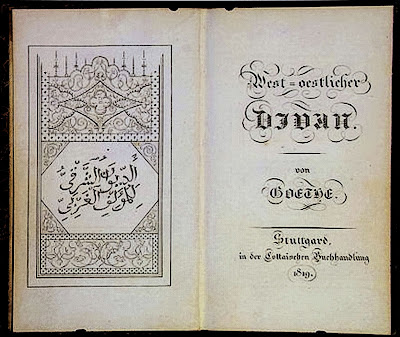

Goethe loved wine so much that he dedicated a Schenkenbuch (tavern book) to it in his West-Eastern Divan. This is a blatant case of blasphemy because, for a devout Muslim, drinking alcohol is forbidden.

Questioning the eternity of the Koran, as in the following excerpt from

the West-Eastern Divan, makes Goethe an unprotected game for devout

Muslims once and for all.

|

Ob der Koran von Ewigkeit sey? Darnach frag' ich nicht! Ob der Koran geschaffen sey? Das weiß ich nicht! Daß er das Buch der Bücher sey Glaub' ich aus Mosleminen-Pflicht. Daß aber der Wein von Ewigkeit sey Daran zweifl' ich nicht. Oder daß er vor den Engeln geschaffen sey Ist vielleicht auch kein Gedicht. Der Trinkende, wie es auch immer sey, Blickt Gott frischer ins Angesicht. |

Is the Koran eternal? I do not ask! Was the Koran created? I do not know! That it is the book of books I believe that out of Muslim duty. But that wine is from eternity I do not doubt. Or that it was created before the angels Perhaps it is a poem, neither. The drinker, whatever it may be, Looks God more freshly in the face. |

|

|

The sick Heinrich Heine. Pencil drawing by Charles Gleyre, 1851 |

|

Mir lodert und wogt im Hirn eine Flut Mir lodert und wogt im Hirn eine Flut Von Wäldern, Bergen und Fluren; Aus dem tollen Wust tritt endlich hervor Ein Bild mit festen Konturen. Das Städtchen, das mir im Sinne schwebt, Ist Godesberg, ich denke. Dort wieder unter dem Lindenbaum Sitz ich vor der alten Schenke Der Hals ist mir trocken, als hätt ich verschluckt Die untergehende Sonne. Herr Wirt! Herr Wirt! Eine Flasche Wein Aus Eurer besten Tonne! Es fließt der holde Rebensaft Hinunter in meine Seele Und löscht bei dieser Gelegenheit Den Sonnenbrand der Kehle. Und noch eine Flasche, Herr Wirt! Ich trank Die erste in schnöder Zerstreuung, Ganz ohne Andacht! Mein edler Wein, Ich bitte dich drob um Verzeihung. Ich sah hinauf nach dem Drachenfels, Der, hochromantisch beschienen Vom Abendrot, sich spiegelt im Rhein Mit seinen Burgruinen. Ich horchte dem fernen Winzergesang Und dem kecken Gezwitscher der Finken - So trank ich zerstreut, und an den Wein Dacht ich nicht während dem Trinken. Jetzt aber steck ich die Nase ins Glas, Und ernsthaft zuvor beguck ich Den Wein, den ich schlucke; manchmal auch, Ganz ohne zu gucken, schluck ich. Doch sonderbar! Während dem Schlucken wird mir Zu Sinne, als ob ich verdoppelt, Ein andrer armer Schlucker sei Mit mir zusammengekoppelt. Der sieht so krank und elend aus, So bleich und abgemergelt. Gar schmerzlich verhöhnend schaut er mich an, Wodurch er mich seltsam nergelt. Der Bursche behauptet, er sei ich selbst, Wir wären nur eins, wir beide, Wir wären ein einziger armer Mensch, Der jetzt am Fieber leide. Nicht in der Schenke von Godesberg, In einer Krankenstube Des fernen Paris befänden wir uns - Du lügst, du bleicher Bube! Du lügst, ich bin so gesund und rot Wie eine blühende Rose, Auch bin ich stark, nimm dich in acht, Daß ich mich nicht erbose! Er zuckt die Achseln und seufzt: "O Narr!" Das hat meinen Zorn entzügelt: Und mit dem verdammten zweiten Ich Hab ich mich endlich geprügelt. Doch sonderbar! Jedweden Puff, Den ich dem Burschen erteile, Empfinde ich am eignen Leib, Und ich schlage mir Beule auf Beule. Bei dieser fatalen Balgerei Ward wieder der Hals mir trocken, Und will ich rufen nach Wein den Wirt, Die Worte im Munde stocken. Mir schwinden die Sinne, und traumhaft hör Ich von Kataplasmen reden, Auch von der Mixtur - ein Eßlöffel voll - Zwölf Tropfen stündlich in jeden. |

A Flood Blazes and Surges in My Brain A flood blazes and surges in my brain Of forests, mountains, and meadows; Out of the mad jumble, at last, emerges A picture with firm contours. The little town that floats in my mind, It is Godesberg, I think. There again, under the linden tree I sit in front of the old tavern. My throat is dry as if I had swallowed The setting sun. Landlord! Landlord! A bottle of wine From your best barrel! The fine vine's gift flows Down into my soul And quenches on this occasion The sunburn of my throat. And another bottle, landlord! I drank The first one in simple distraction, Without any devotion! My fine wine, I beg your pardon. I looked up to the Drachenfels, Which, highly romantically illuminated, Is reflected by the sunset in the Rhine With its castle ruins. I listened to the distant song of winegrowers And the perky twittering of the finches - So I drank absentmindedly, and I didn't think about the wine while drinking. But now I put my nose into the glass, And earnestly, before I sip I look into the glass, but sometimes, Without looking at all, I sip. But strange! As I sip, It occurs to me as if I were doubled, Another poor swallower is Coupled together with me. He looks so sick and miserable, So pale and haggard. He looks at me with a painful sneer, Which makes me strangely nervous. The fellow claims to be myself, We were only one, the two of us, We would be one poor man, Who now suffers from fever. Not in the tavern of Godesberg, In an infirmary Of distant Paris we would be - You lie, you pale knave! You lie; I am as healthy and red Like a blooming rose, I am strong too, beware, That I do not vomit! He shrugs his shoulders and sighs: "O fool!" That has quenched my anger: And with the damned second self I've come to blows at last. But strange! Every puff, I give the guy, I feel in my own body, And I hit myself, bump on bump. During this fatal courtship My throat was dry again, But as I want to call the landlord for wine, Words falter in my mouth. My senses fade, and dreamlike, I hear I hear talk of cataplasms, Also of the mixture - a tablespoonful - Twelve drops every hour in each. |

|

| Preprint of Les Fleurs du Mal with corrections by Charles Baudelaire |

|

ENIVREZ-VOUS Il faut être toujours ivre. Tout est là: c'est l'unique question. Pour ne pas sentir l'horrible fardeau du Temps qui brise vos épaules et vous penche vers la terre, il faut vous enivrer sans trêve. Mais de quoi? De vin, de poésie ou de vertu, à votre guise. Mais enivrez-vous.; |

GET DRUNK You have to be drunk all the Time. That's the only question. If you don't want to feel the horrible burden of Time shattering your shoulders and bending you down to earth, you've got to get drunk all the Time. But of what? Wine, poetry, or virtue, as you wish. But get drunk. |

|

Et si quelquefois, sur les marches d'un palais, sur l'herbe verte d'un fossé, dans la solitude morne de votre chambre, vous vous réveillez, l'ivresse déjà diminuée ou disparue, demandez au vent, à la vague, à l'étoile, à l'oiseau, à l'horloge, à tout ce qui roule, à tout ce qui chante, à tout ce qui parle, demandez quelle heure il est; et le vent, la vague, l'étoile, l'oiseau, l'horloge vous répondront: « Il est l'heure de s'enivrer! Pour n'être pas les esclaves martyrisés du Temps, enivrez-vous; enivrez-vous sans cesse! De vin, de poésie ou de vertu, à votre guise. » |

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace, on the green grass of a ditch, in the dreary solitude of your room, you wake up, your intoxication already diminished or gone; ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that rolls, everything that sings, everything that speaks, ask what time it is; and the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock will answer you: "It's time to get drunk! To avoid being slaves martyred by Time, get drunk; get drunk all the time! Wine, poetry, or virtue, as you wish." |

**

No comments:

Post a Comment