Only some events were rescheduled for 2021; new ones were scarce. On Saturday, July 10, citizens could visit "Freiburg's center and its four cardinal points": In the center Haslach with a juice reception, in the north Hochdorf's picnic mile, in the west Munzingen and a wine fountain, in the east Ebnet offering games and riddles, and in the south guided walks in Günterstal.

Red Baron took the last option.

On Monday, the Badische Zeitung reported about the Günterstal walking tours,

"Who knows, for example, that the philosopher

Edmund Husserl, ex-prime minister of Baden-Württemberg

Hans Filbinger, and the mathematician

Ernst Zermelo

are buried in the local cemetery? Two participants came at 9 a.m., and 15

came for the three other tours."

I was there in the not-so-early morning hour together with a lady. Our

competent guide was the vice president of the local civic association.

Indeed, we three started at the cemetery. Here are the tombs of Husserl and Filbinger.

Indeed, we three started at the cemetery. Here are the tombs of Husserl and Filbinger.

The first documented reference to Günterstal Abbey dates back to September 15, 1224, when the Bishop of Constance inaugurated a new altar in an as-yet unfinished nunnery chapel. A nobleman of the nearby Burg

Kybfelsen ought to have founded the abbey for his daughters

Adelheid and Berta, who were joined by other women seeking to live in a

monastic community, i.e., a Cistercian monastery.

Line 2 leaves Germany's southernmost streetcar terminus for downtown

Freiburg. To the right is Günterstal's traditional restaurant, Kybfelsen, with the buildings of the former Cistercian monastery in the background.

|

|

In memory of Edith Stein, canonized in 1998 as co-patroness of Europe.

The philosopher stayed here when living at 4 Village Street, preparing for her doctorate in July 1916. |

Then we walked along the historical village wall that once had surrounded

Günterstal.

We passed a house where Herbert Marcuse had lived from 1928 until 1933, when he had to flee Nazi Germany.

In Freiburg, Marcuse was part of Martin Heidegger's inner circle of students. On the one hand, he admired Heidegger's "concrete philosophy" and demanded, like him, a "destruction "of the previous history. On the other hand, he criticized Heidegger's individualism and his lack of concern for the material constitution of history.

We passed a house where Herbert Marcuse had lived from 1928 until 1933, when he had to flee Nazi Germany.

In Freiburg, Marcuse was part of Martin Heidegger's inner circle of students. On the one hand, he admired Heidegger's "concrete philosophy" and demanded, like him, a "destruction "of the previous history. On the other hand, he criticized Heidegger's individualism and his lack of concern for the material constitution of history.

Consequently, Heidegger rejected

Marcuse's critical habilitation thesis, "Hegel's Ontology and the Foundation of a Theory of Historicity." Nevertheless, Heidegger had Marcuse's paper published in 1932. In 1984,

five years after Marcuse's death, a colleague, Jürgen Habermas, referred to Marcuse as the "first Heidegger Marxist."

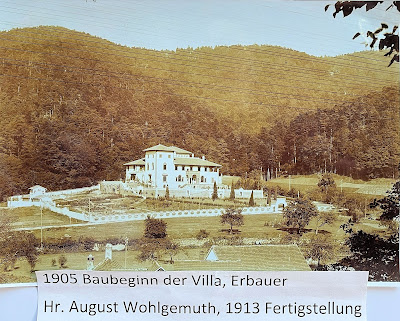

Between 1905 and 1913, Oberamtsrichter (senior judge) August Wohlgemuth had his mansion built in the Tuscan style above the village of Günterstal on land that had formerly belonged to the Cistercian monastery.

|

| Subtropic vegetation |

Indeed, Freiburg's southern suburb, Günterstal, is the ideal environment for

such a building.

In the aftermath of the lost First World War, some Catholic women in Freiburg founded a charitable congregation dedicated to alleviating the misery in the town. In 1922, they requested recognition as a Benedictine order from the pope. Was history repeating?

|

| The traditional entrance to the monastery |

In the same year, Wohlgemuth had to sell his estate. The ladies bought the premises and moved in. They chose

St. Lioba

as their patroness, manifesting that their congregation was not introspective and devoted to ora et labora alone, but an order facing the world. In 1927, the pope gave his placet.

|

| Abbess St. Lioba with her shepherd's crook |

|

| St. Benedict with his shepherd's crook |

|

|

Don't neglect love. The congregation's motto is below its coat of arms. |

Today, 37 Benedictines (Ordo Sancti Benedicti) live in St. Lioba, but the population is aging fast. When the number becomes too low, monasteries can no longer manage the costs and are forced to close. This happened to the Franciscan monastery in my Wiehre district in 2013.

It happened again at the Dominican (Ordo Praedicatorum) nuns' monastery in Neusatzeck, near Bühl in the Black Forest. They were 16, with two of them needing care. They had to sell their premises and found a warm welcome at St. Lioba's in the spring of this year.

|

| ©Ingo Schneider/BZ |

*

No comments:

Post a Comment