After the Big Bang, the universe cooled down to 2.7 K. Yet an afterglow of the hot Big Bang can still be detected.

The measurements of this cosmic microwave background can only be reconciled with theoretical calculations by assuming the existence of Dark Matter.

Therefore, we are looking for invisible and cold matter that does not or hardly collides and is stable. Dark Matter is "dark" because it doesn't emit or absorb light or interact otherwise. Why should DM interact with a detector?

Many theories of Dark Matter, including those that modify the general theory

of relativity (the gray area on the right in the

diagram), allow experiments and calculations to agree without the

assumption of DM.

Since we cannot make any statement about the mass and type of DM, we must search for it in the entire energy spectrum. Experiments are currently conducted at the CERN LHC to detect dark matter in the energy range from keV to 7 TeV. In the lower energy range - Red Baron read zeV for the first time - Dark Matter should be ultralight.

One detector in which the University of Freiburg is involved is the XENONnT, located deep under the Italian Massif Central Grand Sasso. Measurements have been taking place there since 2020. Liquid xenon gas is an excellent scintillator and can be easily ionized.

XENONnT is an upgrade of the XENON1T detector. Prof. Schumann presented the audience with a world record for the new detector. It has the lowest background of all other DM detectors. The double beta decay of 136Xe with a half-life of 2.1 × 1021 years and the neutrino double electron capture of 124Xe with a half-life of 1.8 × 1022 years are clearly identified.

No significant Dark Matter signal has yet been found:

- in the XENONnT detector

- in the particle detectors at CERN

- in the IceCube detector at the South Pole

- in the XENONnT detector

- in the particle detectors at CERN

- in the IceCube detector at the South Pole

Outlook

The existence of Dark Matter proves that previously unknown physics must

exist.

Detection of DM and measurement of its properties are among the most important open questions in particle physics.

More sensitive (larger) experiments are already being planned.

- Broad scientific program also beyond Dark Matter

Additionally

- further Dark Matter candidates

- alternative approaches, new strategies

27 % of it is Dark Datter

-> does not absorb or emit light

-> does not absorb or emit light

We do not know what DM is

Various methods for searching:

-> scattering from atomic nuclei

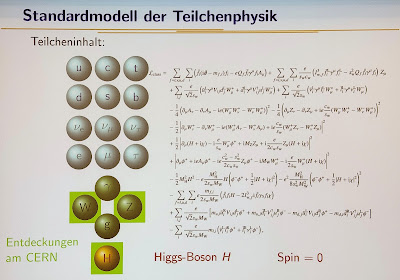

-> production at the accelerator, e.g. CERN

-> Search for annihilation products

-> production at the accelerator, e.g. CERN

-> Search for annihilation products

Challenge: minimizing background signals

So far, Dark Matter has not been found.

-->The search continues!

*